WHY THIS WRITER?

BRINGING SOCIOLOGY AND NEUROANATOMY TO SCREENWRITING

In addition to writing, I am an actor. I am probably not a very good actor, but by taking Acting I (DRAMA 130), Acting II (DRAMA 231), and Voice and Diction (DRAMA 110) from Professor Tracy Williams, and Acting for Camera (DRAMA 148) from Professor John Walcutt at the MiraCosta College Drama Department, I know enough about acting to have, what acting teacher Uta Hagen (1919-2004) called “Respect for Actors.” I have studied enough about acting and attempted enough acting to know that those people that have devoted enough effort to transform their talent for acting into great acting craft deserve credit for their devotion to the profession of acting.

In addition, while studying sociology for nine years as a Master’s and Ph.D. candidate, I learned about “social psychology,” the study of how people think when they are in groups from Dr. Dennis Waskul at MInnesota State University Mankato, and “ethnomethodology” the study of how people act in groups , from the late Dr. Albert “Britt” Robillard (1943-2015), a distinguished protegee of Harold Garfinkel (1917-2011), the originator of “ethnomethodology.” I also learned much about “neuranatomy”" the study of how the brain functions, by working with Dr. Milton “Mickey” Diamond (1934-2024), at the University of Hawai’i J.A. Burns School of Medicine.

To illustrate, here is a video presentation I made for Britt’s “Seminar on Social Structure and the Individual” (SOC 741) titled Awkward Moments: Involuntary and Voluntary Motion in Social Interaction (2007). Perhaps the first example of my filmmaking career, Awkward Moments uses scenes from the acting of Woody Allen and Diane Keaton in Annie Hall (1977) to show how cognition, analysis, and physical actions are linked through our brains.

Thus through this short film, I linked social psychology with neuroanatomy. Moreover, although I was then only 41, my interest in telling stories without dialogue is already manifest. In Ticket to Kyiv, an English-language film in which much of the dialogue is in Ukrainian, the actors must use every skill they have besides speech to tell the story.

If the result leaves the audience no more confused than Rachel, a young American that doesn’t understand Ukrainian, they are immersed into the story and taking Rachel’s role, and not merely observing the scene as outsiders. This is part of what makes Ticket unusual and unconventional.

For better or worse, I believe I bring to screenwriting and directing a set of knowledges that no one has before.

ACTIONS AND REACTIONS BY HUMAN BRAINS

To fully employ Method Writing, Acting, and Directing, one should have a working understand of how the human brain functions.

The body is the instrument the cortex uses to express its will, and the amygdala, cerebellum, and brain stem—the latter being the channel through which passes all motor functions the cortex decides to attempt—control the body unconsciously and subconsciously. The best results from using the methods of Konstantin Stanislavski (1863-1938) in writing, acting, and directing come from consciously attempting to duplicate the conscious, subconscious, unconscious functions of the imaginary brain of the imaginary character represented on the page and set.

A functional diagram of the human brain. Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Australia.

In the illustration above, the pink area represents the “cerebrum,” the “thinking” part of our brains. Within its billions of neuron cells are all our senses, our analyses, and our memories. Its activity when we are nearly-conscious form our “dreams.” The outer layer of the cerebrum, called the “cortex," is where our immediate thoughts are handled.

The Cerebellum colored purple controls all motor functions. Note its direct connections to the brain stem and the cerebrum.

The part labeled “brain stem” is sometimes called the “lizard” part of our brains. This section manages all the functions of our bodies that are involuntary, like keeping the heart beating, and the lungs breathings. Any decision from the cerebrum to move a limb must run through the brain stem and the cerebellum to get to the muscles of the body. For example, your cerebrum says “Walk to there,” your cerebellum coordinates your feet so you walk without falling, and your brain stem transmits the instructions to your body muscles so your walking is smooth and largely unconscious.

The darker yellow part labeled “amygdala” is the “emotional” part of our brains. The two amygdalae are directly connected to the brain stem and the pituitary gland. The pituitary gland controls the other glands in the body, particularly the adrenal gland that is triggered in an emergency.

What [a] piece of work is a man! How noble in reason, how infinite in faculty! In form and moving how express and admirable; In action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god! The beauty of the world, the paragon of animals!

Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2

Hamlet, Act V, Scene 2, Hamlet and Horatio, Victor Müller (1829–1871). (CC) Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-Upon-Avon, England.

As remarkable as it may seem, the functions of the amygdala operate on only three axes: “Lust” (or Desire), “Fear,” and “Anger.” All emotions, including positive ones like “Contentment” and “Euphoria,” are different combinations of these three basic responses:

For example, imagine that you are driving a car that suddenly breaks down in the desert on a hot, dry day. Your rising thirst is the result of your “Lust” for water. Your awareness that you might die of thirst is the result of the “Fear” centers of your Amygdalae being triggered by your cerebrum—the part that is thinking, subconsciously if not consciously, about your increasingly dangerous situation.

Finally, suppose that the only reason you are on this lonely desert road is that someone told you it is a “short-cut” and that using it is safe. As your “Fear” center is triggered more and more, the “Anger” center of your amygdalae is more likely to be set off also. Some people will swing into anger the moment the car breaks down, while others will never cease to blame themselves and only “get angry” at themselves. The amygdalae are a remarkable part of our individual “personality.”

(Chinese Man) Dying of Thirst in the Mojave Desert. Illustration by Frederick Remington, 1891.

The fact that the cerebellum ana amygdalae are physically closer to the brain stem than the cerebrum help explain why we often—some more often than others—say and do things that we later, often immediately, regret. The phrase, “I acted without thinking,” or “I didn’t know what I was doing” are often honest descriptions of what actually happened.

All of this leads to what I call “Action-Reaction Theory” in dramatics. A performance on a theatrical or film set should be more than actors reading a set of lines and performing a series of action as directed from a script. Rather than treat the reading of a line by an actor as a literal “cue” to read one’s next line from a script, actors should treat each line they hear as though it were an original and most-likely unexpected statement, inquiry, or declaration by another other actors.

Moreover, they should react appropriately to what they just heard or saw, with or without words. The believability of reactions by non-speaking actors usually determine whether or not the audience continues to “suspend their disbelief” that they are watching real people interacting in front of them. This is why I believe the best actors display their ability without saying a word; their reactions are more important than whatever they say.

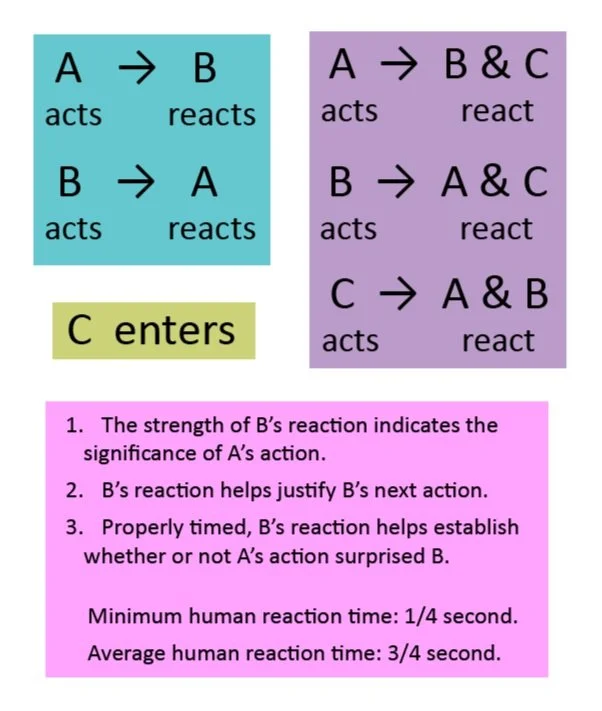

Illustration of “Action-Reaction Theory” by Hannah Miyamoto. Produced for Script Analysis for Performance and Design (DRAMA 123) by Professor Sean Fanning, MiraCosta College, October 2024.

Furthermore, before saying anything in response to another actor, a good actor should at least start their physical response and actions before speaking. In addition, they should not anticipate the other actor’s previous actions, but respond to them after the action.

As the accompanying illustration shows, the amount of delay before reacting to acts by another actor depends on the nature of that act. The strength of that reaction indicates, and helps establish significance of the action that prompted the reaction. The amount of delay between action and reaction helps establish whether the action was a surprise or expected.

For example, if “A” picks up an object and throws it at “B,” the amount of time before “B” tries to dodge the projectile is very short, i.e., as little as one-quarter of a second. If instead, “A” makes a cleverly cutting remark with dual interpretations, “B” may be justified in taking one or two seconds before responding with a mocking scoff, look of resentment, or a verbal statement in response.

These rules apply to the production of convincing drama. Comedy and especially farce are deliberately unrealistic with brisk rapid banter. The Marx Brothers created an air of surreality in their comedy (see example), with their wise-cracks seeming to land on ears deaf to the insults they spewed.

Rufus T. Firefly: I could dance with you until the cows come home. On second thought, I'd rather dance with the cows until you come home.

Duck Soup (1933). Written by Bert Kalmer and Harry Ruby.

MY THEORY OF METHOD WRITING

With all due respect for Jack Grapes, the actor-writer that originated the term:

When stripped of its false mystique, “Method Writing” is the process of studying and understanding (in a loose Verstehen sense, to use the term of sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920)) the thoughts of the characters, before writing what they say and do. Like “Method Acting,” as Konstantin Stanislavski (1863-1938) developed it, “Method Writing” requires writers to understand the knowledge, feelings, and goals of each of their characters so that what they say and do naturally reflects the thoughts of the character.

“Method Writing” is superior to conventional story-telling that focuses on plot and description rather than the thoughts and perceptions of characters. Inevitably, focusing on plot over characters tends to lead to stories that are unbelievable and unsatisfying. However “Method Writing” demands much more research and analysis, just as “Method Acting” requires actors and directors to learn what the character would know, think, and feel, if they were a living person. Through that analysis, dialogue and actions of characters flow naturally, believably, and engagingly.

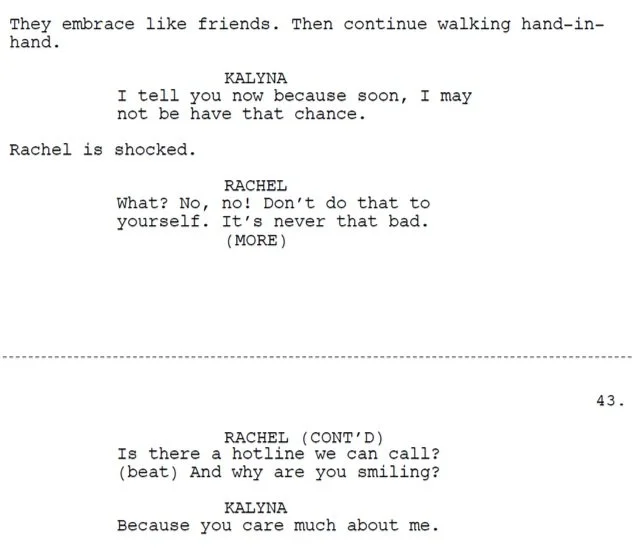

Excerpt from Scene 47, Ticket to Kyiv.

The accompanying passage from Ticket to Kyiv illustrates “Method Writing” by demonstrating the consequences of two characters not having the same understanding of their present condition and activity, or “definition of the situation.” “Definition of the Situation” is an important element in the sociological theory of “Symbolic Interactionism.”

At the start of the scene (Scene 47, p. 41-42) Kalyna and Rachel reveal to each other their mutually attraction to the other, and on a Kyiv street, they share their first kiss. They then walk along the sidewalk some more before Kalyna reveals that she might be dead soon.

Rachel, and the audience, naturally think that Kalyna is contemplating suicide, now that she knows she is lesbian. However, Kalyna is only trying to inform Rachel that she has decided to do something dangerous: Help bring back wounded soldiers from the front line.

Rachel responds to Kalyna’s words by panicking, frantically trying to think of a way to convince Kalyna not to kill herself. Only when she sees Kalyna smile does she realize that her girlfriend is not suicidal. However, Kalyna smiles because to express her happiness in learning that Rachel truly loves her. Until that moment, Rachel had not shared her feelings with Kalyna.

This sequence between Rachel and Kalyna also illustrates the tension-relief mechanism of comedy. Rachel panics when she thinks Kalyna is suicidal, but then she (and the audience) can chuckle when Kalyna reveals that she was trying to say something entirely different. However, she is still attempting something dangerous, something that might be as fatal as suicide.